A Chronicle of Fish & Chips

Posted by Emily on 7th Nov 2023 Reading Time:

To say Mike Pili knows a story or two about fish and chips would be a vast understatement. As he shares a host of anecdotes from more than 60 years of experience in the trade, we can’t help but wonder whether it’s a harder or easier job today.

When Mike’s parents came to the UK from Cyprus in the mid-1930s and then went on to open a fish and chip shop in Birmingham in 1943, it was a very different industry. There were no planning regulations or hoops to jump through to open a takeaway – Mike’s parents simply set up shop in the front room of their house – and there were no trade associations to offer training or advice, just other members of the family who had also gone into the trade.

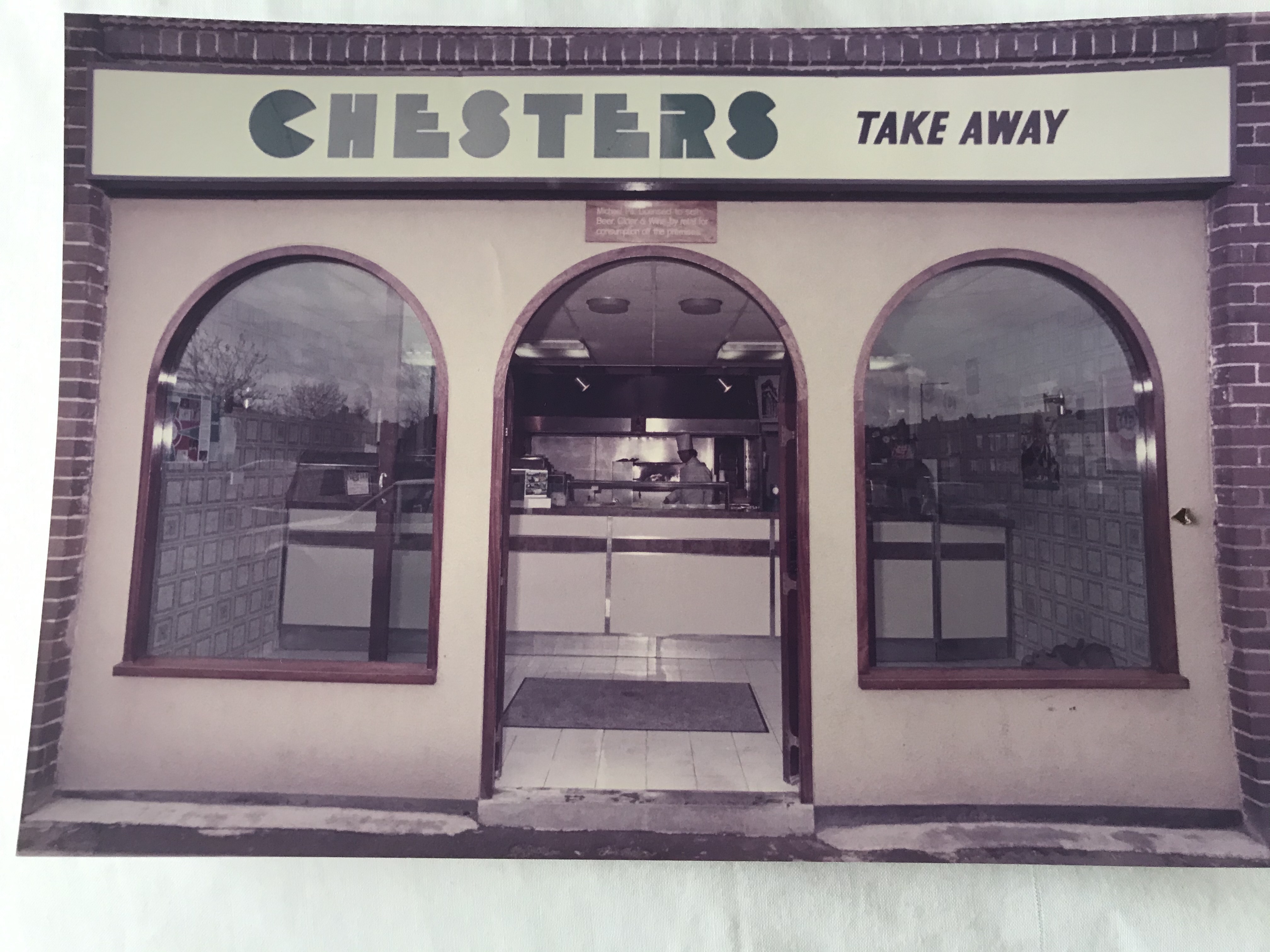

“It’s very different now,” says Mike. “Fish friers today have the chance to produce food and have premises on a par with any other type of catering establishment in the UK or the world. The shop set out, the equipment, the back-of-house, friers can make a super business and it can be run efficiently if they put their minds to having systems in place and training their staff.

“And there’s so much help these days; you’ve got the NFFF, Seafish, Ceres, trade magazines, the internet, associations you can just ring up. If you want to learn, you have plenty of routes.”

Although Mike joined the family business full-time in the 1960s, aged 17, he was a spud boy for many years before. He recalls how he would take his life in his hands each time he operated the potato peeler with its belt on the outside and standing on a wooden box, being too small to reach the handle of the fixed bench chipper without it.

Later, the chipper was replaced with a flatbed electric version, great for cutting chips, but it would jam up with any large potatoes and bits of grit. It was tough to dismantle, and unfortunately, Mike’s mum lost the top part of her thumb whilst cleaning it!

Having access to a regular supply of chips and batter bits, Mike was always popular at school. He remembers how locals would bring in newspapers – because, in those days, there were no offcuts – with the reward being a bag of warm scratchings. While they tucked in, Mike would cut the newspapers into small squares, a practice that continued until they started using old newspapers that were returned to the local newspaper offices due to misprints. Eventually, a halt was put to this in the ‘70s when it was deemed unhygienic to use any newspaper.

With thermostats only being introduced to ranges in the late ’60s, being ready for the lunchtime trade involved an element of guesswork. “We had a coal-fired range in those days, and you had to know when to put the fish in the pan,” says Mike. “It was said, and I never saw this, that people would spit in the pan to see if it was hot enough. What I used to see, though, was my mum dropping some batter or a chip in to see the reaction with the fat. You knew then when to turn the range down. You had to stand and watch the product.

“And I remember to cool the pan down at night; my mum would peel whole potatoes and drop them in the pan. The next day, when she restarted the range and heated the fat, the potatoes would come out as roast potatoes.

“I think that was one of the reasons fish friers used to pour chips over the fish when they were frying – to dampen down the heat of the fish. When you put the fish in, there was a certain point during frying when you’d have to turn off the range or the heat would keep going up and up. You’d then have to turn the range back on to complete the frying.”

The menu in those days wasn’t as vast as it is today. Fish and chips plus a portion of peas, if you were lucky, were the standard fare. The selection of fish would give many shops today a run for their money with cod, haddock, whiting, plaice, skate and hake all popular – and all coming skin-on and bones-in.

“People would ask for whole plaice,” says Mike. “So we would de-head it, cut it, gut it and cook it whole. Hake was popular, too. We would cut it into three: the top part, we would take the bone out, the middle bit was called the round hake, and the bottom bit would be called the tail hake. People would order in advance which section of the hake they wanted. Round hake was always popular, as was the tail hake, and they were both served with the bones still inside. It wasn’t until the ‘60s when we started taking the bones out of the cod.”

Unlike today’s friers, Mike didn’t have the luxury of fish being delivered to his door. Instead, he would make the two-mile journey with his dad to the fish market in Birmingham but, with no transport of their own, on occasions it was problematic.

“I remember one day, we jumped on the bus to come back and the conductor said we had “obnoxious products” on us so he chucked us off and we had to walk home!”

There were several times of the year when fish and potatoes were simply unavailable. At Christmas, for example, when the Scottish fleet took a holiday, there would be no fish, something friers would try and get round by freezing their fresh supplies.

“It wasn’t interleaved, so when it defrosted it was an utter mess,” recalls Mike.

During the mid-60s, frozen fish was introduced to the trade, made up of reformed fish and cut into oblong sizes by bandsaw. Without any guidance on how to fry from frozen or defrost and being a lot smaller than current sizes, this did not take off in the Birmingham area.

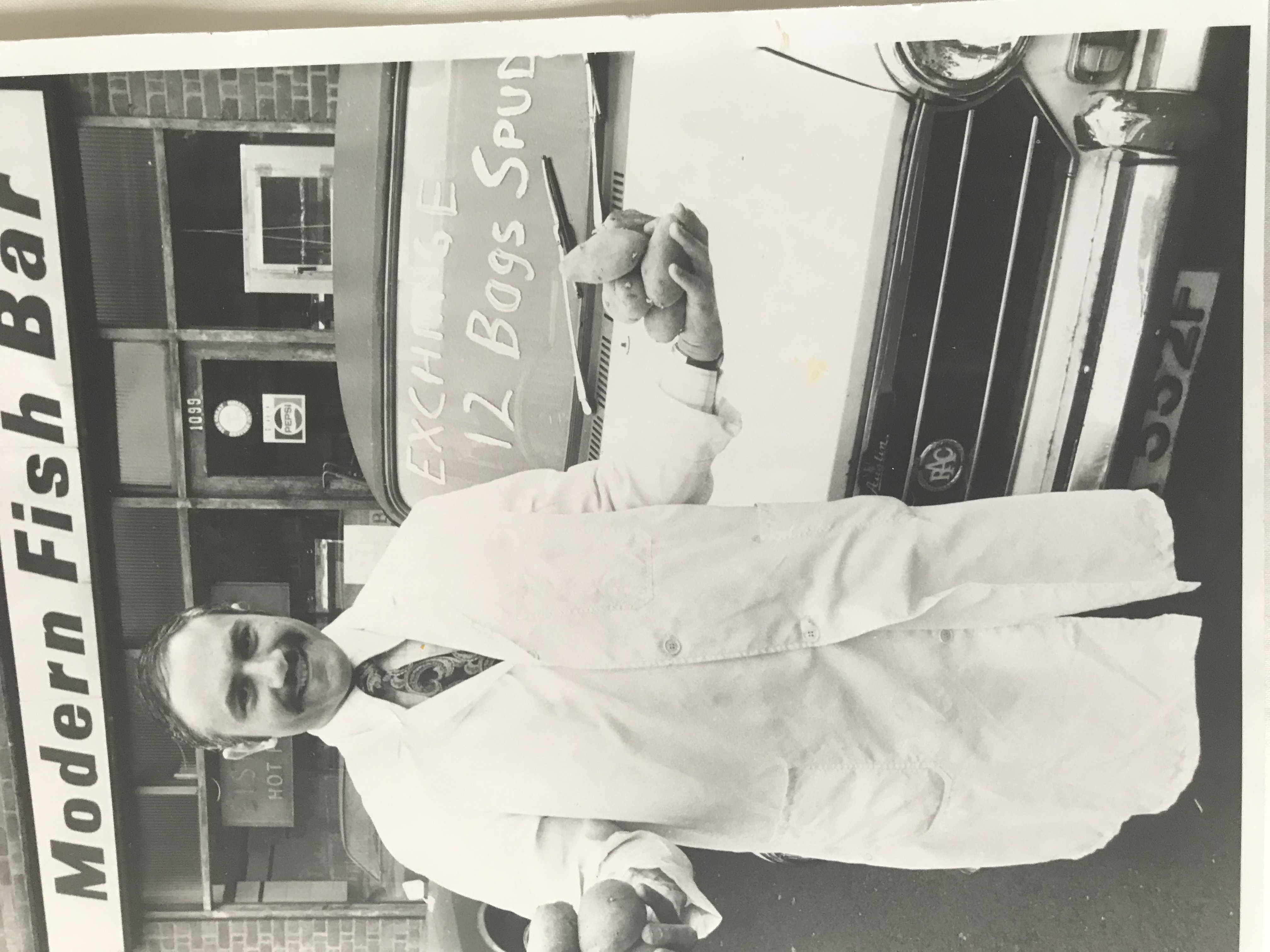

Potatoes proved equally tricky to source, especially when moving from the old crop to the new. “It wasn’t like today where you get a pretty good transition from old to new, and the potatoes come out a decent size. These would be quite small, and the bags were full of stones and soil.

“We used to get around it by importing potatoes from France, Egypt and Cyprus between the two seasons. They would come in a hessian sack, and they would be 112lb (50kg) bags, so a lot heavier than today’s 25kg sacks.”

Mike also recalls when purple potatoes started surfacing in fish and chip shops due to the unscrupulous behaviour of some keen to make a quick buck. Mike explains: “Potatoes used to be grown by levy and set acreage, so farmers were guaranteed a set price for their crop. If they didn’t sell all the potatoes at the end of the season, they were covered in purple dye and sent for pig food. Some people would put them on the back of a lorry and go around the chip shops trying to sell them. Officers from Weights and Measures would come round the shops checking for purple potatoes!”

Undeodorised dripping was the frying medium of choice back then, and Mike recalls during the ‘50s and ’60s being encouraged to buy fat that came in a plain brown box. It turned out to be fat stockpiled by the government during the war and was being released into the food industry before it became obsolete.

Another memory that raises a chuckle now but which at the time was the cause of much frustration was the exercise of writing the menu on the inside of the windows using chalk and flour.

“We would write the names of the fish on a bit of paper, look at it in the mirror, see how to do the words and then write it on the

window so it could be read from the outside. But when we fried, because we had no extraction, whenever you opened the lids on the pans, the shop would fill up with steam, and the windows would start to run. So, each morning, we would have to clean the windows and start again.”

It wasn’t just a lack of extraction that posed a challenge for fish and chip operators at the time; they also had to navigate serving a queue of customers with frying ranges that didn’t have heated cabinets.

“Back in those days, we would have a queue outside the door before we opened at 12 o’clock for lunch. We shut at 2 pm and then opened again at 5 o’clock, which coincided with all the local factories finishing. You’d hear all the hooters go off to signal the end of the day. We had no way of keeping the food warm, so we put the fish into racks, and when someone walked in, we would drop the fish back into the hot fat. It’s a practice still carried on in Ireland.”

Although Mike knew no better at the time, he looks back now and is appreciative of the enormous leaps forward the industry has made.

“I hate to hear people saying fish and chips today is difficult because I’ve seen what we went through. Today, you get fish in all different sizes; it come boned, skinned, and cut for you. Potatoes are coming to you cleaner, there’s no soil, and farmers want to produce a good quality product. You’ve got a choice of potato varieties now, and if you don’t want to do your potatoes, you can get them ready, chipped, and peeled. Frying ranges make the whole frying process so much easier and remove a lot of the skill that was once needed.

“But having said that, there is much more for friers to understand and be aware of now. There are regulations, health and safety, HACCP, training, and marketing. These aspects weren’t an issue to us, so in that respect, it’s not an easier business.”

Mike appreciates, too, that he was fortunate to work at a time when competition just wasn’t an issue. Yes, there were 20,000 more fish and chips shops, but without transport, you stuck to the closest one, the one you could easily walk to.

“The competition today is so fierce, not only from fish and chip shops, but nearly every type of outlet serves food of sorts. You have to have something or do something to attract the customer. You have to have a product that people want, which is where quality is so important. We’ve got too many shops selling fish and chips too cheap, and although it sounds good on paper, when you look at the product, it’s no good. It’s better to have a small portion of decently fried fish and chips, peas, for x amount of pounds than double the size for a lot less.

“Unfortunately, we have people selling fish and chips for one that will feed two, and they are losing a sale. They are stuck in this trap. A lot of shops, you just couldn’t eat what they serve in one go. Those shops should transfer what they are selling onto a plate and consider if that’s a portion for one or two.”

One of the toughest challenges to face operators today is the current coronavirus pandemic, which has forced operators to think on their feet and adapt quickly. It’s something Mike can appreciate more so than many.

In the 1970s, he worked through constant industrial strikes, rampant inflation and prices changing weekly. This meant regular wage demands to keep pace, and so the circle went on. The introduction of the three-day week, meanwhile, saw daily power cuts where electricity was switched off for four hours at a time. Mike, being a conscientious businessman, invested in a generator to ensure he could keep trading.

“I worked out which equipment I could have on so as not to overload the generator, and when the electricity went off, I’d switch it on. We were the only premises around that had our lights on, but I couldn’t use the chipper or the peeler then, so we would prepare that all beforehand. And if we wanted to use the microwave, I would have to turn something off.”

During the gas strikes in the same decade, Mike recalls going without gas for two weeks. Rather than shut the shop, he bought a Valentine fryer and a rotisserie oven and served chicken and pies on what today’s friers would call a click-and-collect basis.

“On a Sunday, I would open and take orders so I could load up the machines, cook everything in the morning, and at lunchtime, people that had already pre-paid would come and collect their food. It was one way to stay open.

“It taught me that whatever disaster hits you, you either do nothing and accept it or you get up and you act. We didn’t make much money, but we survived, and people remembered us for what we did.”

Just as Mike survived back then, he applauds those who have had to flip their businesses to collection and delivery at a moment’s notice, as well as those who have implemented all the correct social distancing measures to stay open safely.

“Friers have been marvellous through the pandemic; they’ve been so resilient. I feel sorry for the shops that are restaurants only, and for the shops that are in tourist areas, but, on the whole, the rest haven’t come out too badly in the sense they still have a business to run. Yes, they’ve had to adapt overnight to new ways, but fish friers quickly worked out how to put in measures to keep customers and staff safe. Things that would’ve happened to our trade-in five or ten years ago have been hastened quickly – click and collect, card payments and deliveries.

“Many have realised, too, they can do the same sort of business in shorter hours; they are now not so afraid of putting their prices up, of switching packaging, of not selling this product or that. These are all things I think will stay and that have been positive for our industry.”

What a lot of people won’t know is that Mike lived through his own corona problem during the ’60s and ’70s, adding: “Corona was a brand of a popular pop. When standing on shelves in a hot shop, the tops would explode, and the pop spilled out; sometimes, the glass bottle would shatter.”

Over the years, Mike’s witnessed a fair few occasions where fish and chips have been written off. And while he can see there being a natural cull of shops due to economics and natural progression, he’s confident the fish and chip industry will not only survive but forge forward.

“It’s a great situation we have today. OK we don’t have 35,000 plus shops as we did back in the ‘30s, but I think friers today are much more professional, they are proud to say they are caterers, chefs, purveyors of food. In the past, they were their own worst enemy, saying ‘I’m only a fish frier’, but they are not only a fish frier. They are so much more and they know so much more than just frying fish and chips.

“Fish and chips has a good future. We still have to tweak a few things, we need to look at the packaging, we need to look at making fish and chips healthier, we need to look at portion sizes, but the last 12 months have proved fish and chips has made a come-back. We’re selling more fish and chips than ever before because people have confidence in the food they are buying and the shops they are buying from.”