Unravelling the Mystery of Nitrates in Your Food

Posted by Emily on 29th Oct 2023 Reading Time:

Nitrates often conjure images of chemistry experiments or agricultural fertilisers rather than something you'd find on your dinner plate. However, these compounds are more than scientific curiosities - they're at the heart of a debate about our food and health.

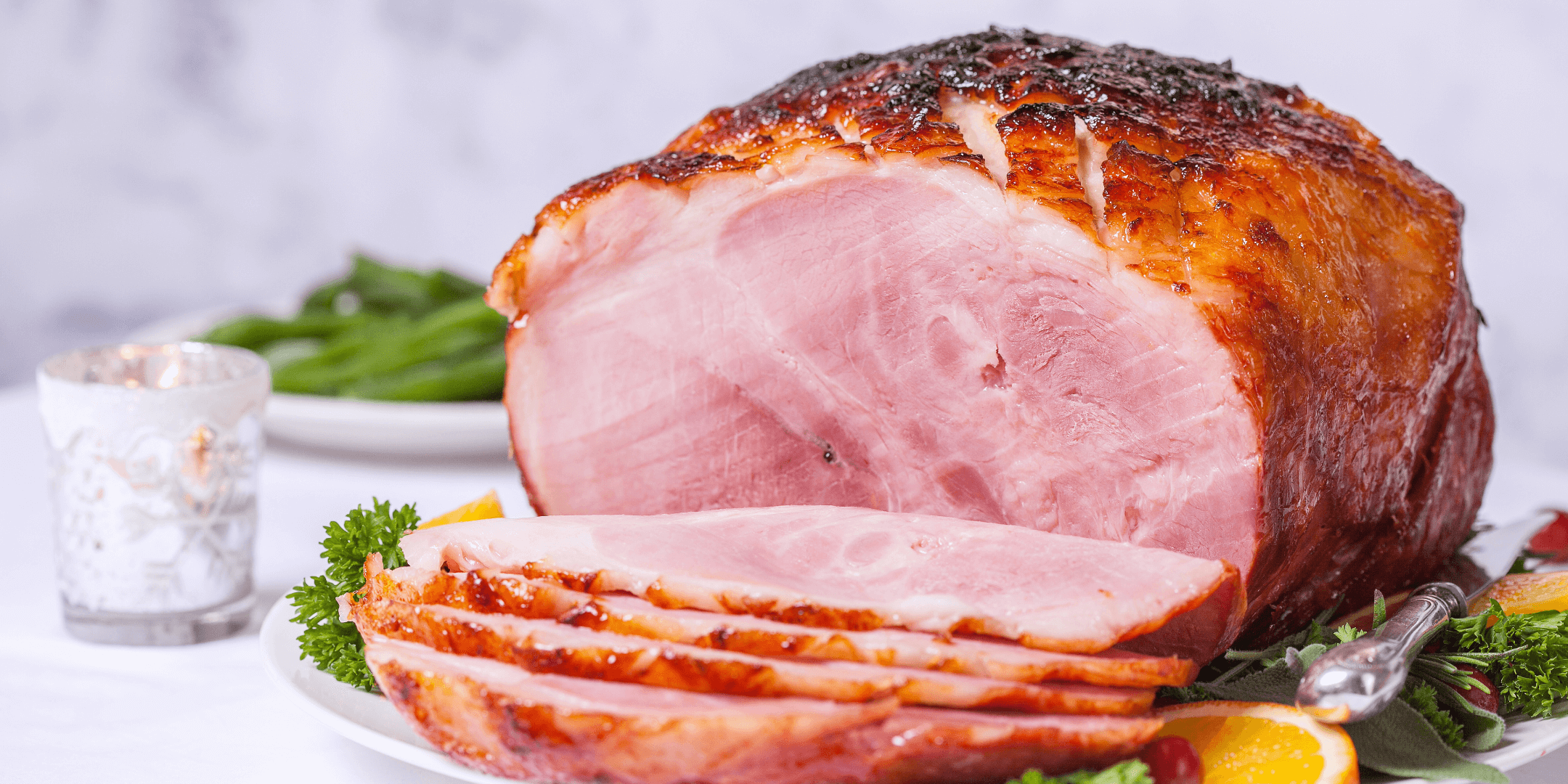

Typically, the mention of nitrates and their close cousins, nitrites, evokes warnings about their presence in processed meats like bacon and ham due to their potential cancer risks. Yet, the narrative is more complex than labelling them 'harmful'. Surprisingly, these same nitrates are celebrated for boosting exercise performance and reducing blood pressure, particularly those naturally occurring in beetroot juice. They're even used in medications for heart conditions such as angina.

So, what's the real story behind nitrates and nitrites?

These compounds, found in various forms like potassium nitrate and sodium nitrite, are part of nature's chemistry set, composed of nitrogen and oxygen. Nitrates have three oxygen atoms attached to nitrogen, while nitrites have two. They're permitted as preservatives in foods like cured meats and some cheeses, keeping dangerous bacteria at bay.

Contrary to popular belief, processed meats are not the primary source of nitrates in our diets. In reality, they contribute just 5% of the average European's nitrate intake, while over 80% comes from vegetables. Plants soak up nitrates and nitrites from the soil, which are naturally occurring minerals or formed by soil microbes decomposing organic matter.

Vegetables such as spinach, rocket, and beetroot juices, as well as carrots, are exceptionally high in nitrates. Interestingly, organically grown produce might contain fewer nitrates due to the absence of synthetic fertilisers.

However, it's crucial to distinguish between nitrates in meat versus vegetables. This difference significantly impacts their potential health effects, especially regarding cancer risk.

Understanding the Cancer Link

In themselves, nitrates are relatively unreactive; however, nitrites and their byproducts actively engage in bodily chemical reactions. While we don't generally consume nitrites, they form when bacteria in our mouth convert nitrates from food. Notably, using antibacterial mouthwash can substantially reduce this conversion.

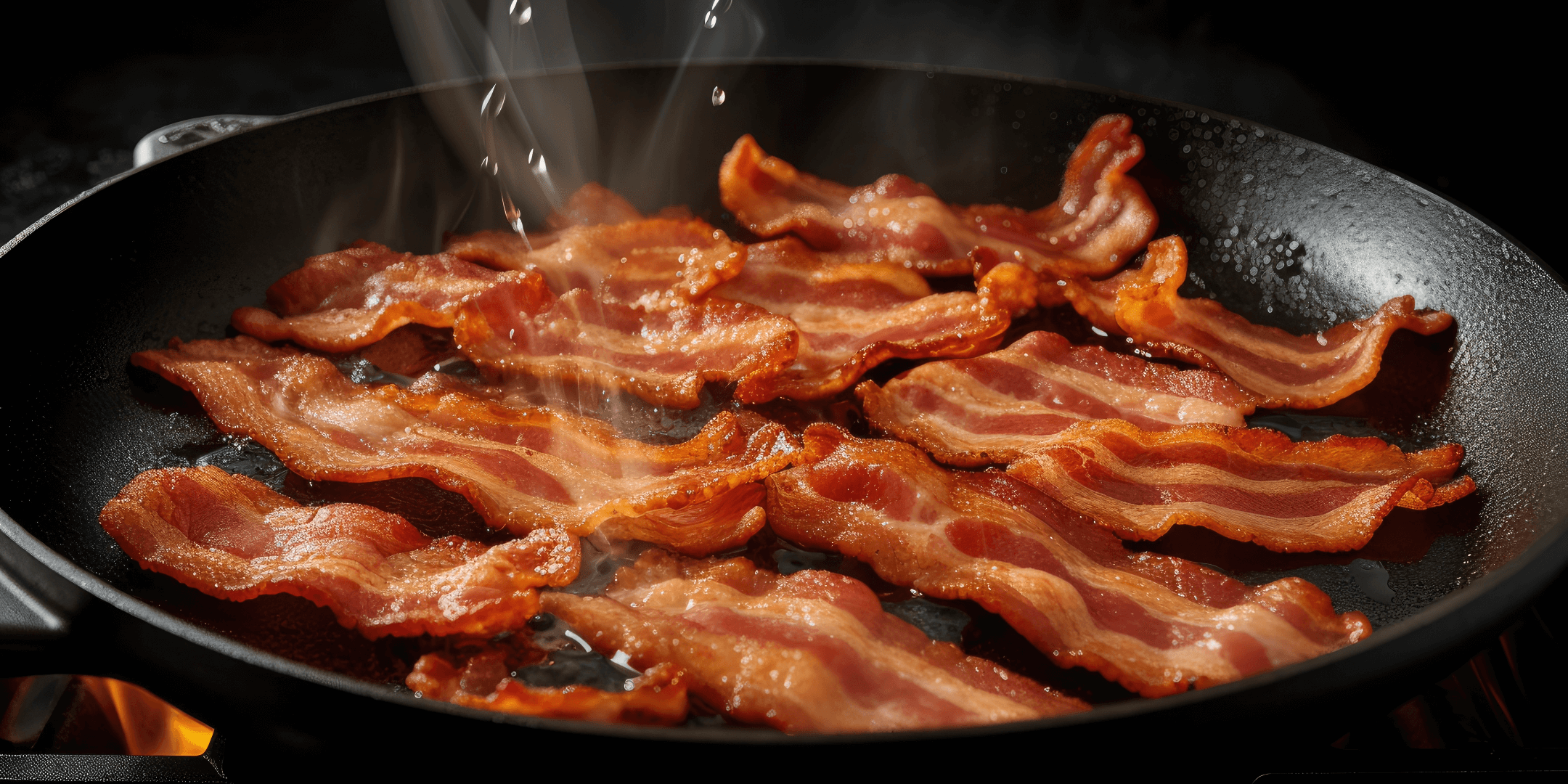

Here's where things get tricky: when swallowed, nitrites can interact with stomach acid and dietary amines (found in protein-rich foods) to produce nitrosamines, notorious for their carcinogenic properties linked to bowel cancer. Cooking methods, especially high-heat processes like frying bacon, can also encourage nitrosamine formation.

Kate Allen, from the World Cancer Research Fund, explains: "It's not so much nitrates/nitrites per se [that are carcinogenic], but the way they are cooked and their local environment that is an important factor. For example, nitrites in processed meats are near proteins (specifically amino acids). When cooked at high temperatures, they can more easily form nitrosamines, the cancer-causing compound."

However, it's essential to put the risks in perspective. Although processed meat is classified as a carcinogen, the associated risk is relatively minor. For instance, in the UK, regular consumption of processed meat (like three daily rashers of bacon) increases one's lifetime risk of bowel cancer marginally, from six to seven in 100.

The Healthier Side of Nitrites

Nitrites aren't universally villainous. They're key players in producing nitric oxide, a molecule with significant benefits for our cardiovascular system. This discovery was so revolutionary that it earned three scientists a Nobel prize in 1998. Nitric oxide expands blood vessels, reduces blood pressure, and fights infections, making it vital for overall health. As people age, the body's ability to produce nitric oxide decreases, making dietary nitrates an important alternative source.

Although the nitrates in your ham sandwich and salad are chemically identical, the latter is the better option. Amanda Cross from Imperial College London emphasises, "We have observed increased risks associated with nitrate and nitrite from meats for some cancers, but we haven't observed risks associated with nitrates or nitrites from vegetables." She attributes this to vegetables' lower protein and higher vitamin C, polyphenols, and fibre content, which inhibit harmful nitrosamines.

Striking the Right Balance

Accurately gauging our nitrate intake is challenging due to the fluctuating levels in food. Gunter Kuhlne of Reading University notes the variability, saying, "Levels can vary up to 10,000-fold for lettuce, and nitrates within drinking water can also vary considerably." This makes studying nitrate's health effects quite complex, as it may simply indicate vegetable consumption.

Though an Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) exists, it's easy to exceed, particularly through diets heavy in processed meats. However, some experts argue for a revision of these standards, advocating higher nitrate levels if sourced from vegetables.

Consuming around 300-400mg of nitrates, equivalent to a generous serving of leafy greens or a shot of beetroot juice, has been associated with health benefits like lowered blood pressure. However, extreme intake (2-9 grams) can be toxic, though such scenarios are rare and typically linked to contaminated water rather than food.

In conclusion, if your goal is to embrace the beneficial side of nitrates and nitrites while steering clear of risks, your best bet is a diverse diet rich in fruits and vegetables, limiting processed meats. This balanced approach will likely tip the scales in favour of health benefits over potential harms.